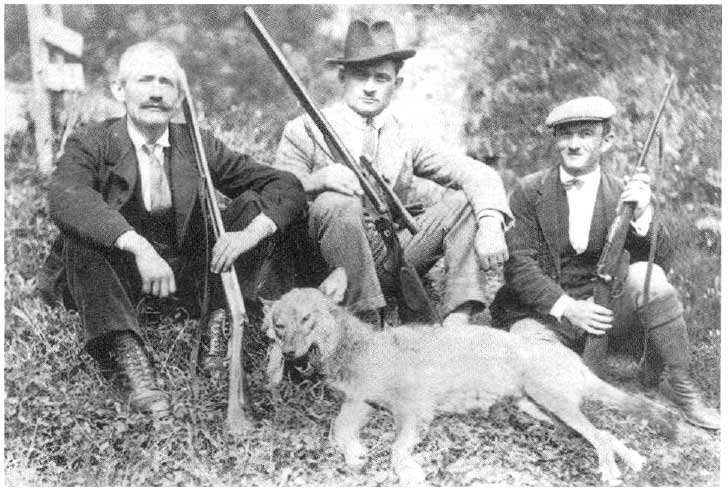

"Mr. Mina Antonio was Giovanni with fatigue and courageous daring on the evening of May 24, 1929 and precisely at 21 pm in the Campu Gon locality he was able alone to hit a furious Wolf in Death who spread terror in a flock of Peccores scattered in those surroundings, At the same moment he managed to save a sinner that the Iron and furious animal had bitten ”. Handwritten note by Mina Antonio himself and affixed as a caption to a picture containing the photographs of the event.

(Tunin and the wolf, Cesco Frare, 2000, image source "The path of the wolves")

With these words of Antonio Mina said Already, the conflict between wolf and man in the north-east of the Italian Alps ends for many decades: in fact, the wolf killed by Tunin on 24 May 1929 in Malga Campo Bon, in Comelico (BL) is the last legal slaughter. The first law for the protection of the wolf dates back to 1971, with the Ministerial Decree "Natali" which effectively excludes the wolf from the list of harmful animals, prohibiting hunting. We will have to wait well over seventy years before recording another presence of the species in the north-east, precisely in Trentino, with the first sighting (in 2006), and then the discovery (in November 2007), of a wolves. inside the Varena Reserve, in Val di Fiemme, by the then Rector of the Augusto Polesana Reserve. From that moment on there have been several reports, in particular in western Trentino, almost always of single wolves from Switzerland or other areas of the western Alps, until 2012, the year in which the first pair was formed within the Regional Natural Park of Lessinia, on the border between Veneto and Trentino, composed of a male wolf of dinaric origin (canis lupus lupus) and a female she-wolf from the Italic population (The dog Wolf).

The pair's first reproduction in 2013 marks a definitive return of the wolf in the north-east of the Italian Alps: since that first herd in 2013 there have been around 17 herds in Trentino at the end of 2020 (see the part relating to the status of the wolf in Trentino and the data from the large carnivores 2020 report available here).

Faced with this rapid growth in numbers and area, also the result of the high potential of the territory, the question of the more or less remote possibility of intervening with killing.

The idea of this article is to give first of all a brief legislative framework of wolf management in Italy and in Europe, to understand within what parameters and through what tools the slaughter is possible.

In the second part of the article we will provide a photograph of the management of the species in some countries bordering Italy and belonging to the European Union, in particular France, Austria e Slovenia.

Finally we will try to understand what could be the consequences of any wolf culling on the numerical trends of the species and on the possible reduction of damage to domestic livestock.

To do this, we asked researchers from three different nations who work on the wolf.

Legislative framework on wolf management in Italy and at European level.

The following are the three main regulations governing the conservation and management of wolves at the Italian and European level, and in particular the Berne Convention (1979), law 157/92 and the Habitat Directive (1992).

Bern Convention 19 September 1979: Convention on the conservation of wild life and the natural environment in Europe L. 08 August 1981, n.503.

La Bern Convention is a binding international legal instrument on nature conservation, which covers a large part of the natural heritage of the European continent and extends to some African states. Its objectives are the conservation of wild flora and fauna and their natural habitats and the promotion of European cooperation in this field. The parties who signed the Bern Convention they undertake to adopt all suitable measures to guarantee the conservation of the habitats, flora and fauna listed in the annexes. Italy has ratified the convention with the law n. 503 of 5 August 1981, which entered into force from 01 June 1982. The wolf falls under Annex II, the one that includes strictly protected species of fauna.

11 Law 1992 February 157, Rules for the protection of homeothermic wildlife and for hunting and provincial Law 9 December 1991, 24.

In Italy, hunting is governed by L. February 11, 1992 n.157: it is a framework law, or a state law that contains the guidelines under which the Regions and the Autonomous Provinces, govern with their own laws the wildlife management and protection. In Law 157/92 the wolf is included among the particularly protected species (art.2 c. 1). Provincial law 24/91, which regulates the "Regulations for the protection of fauna and the exercise of hunting" in the province of Trento, in addition to not mentioning the wolf in the list of huntable species (art. 29 "Huntable species and hunting periods"), all 'art. 2 c.2 refers to Law 157/92 as regards particularly protected species.

Council Directive of 21 May 1992 n.43 Conservation of natural and semi-natural habitats and of wild flora and fauna: “Habitat” Directive DPR 8 September 1997 n. 357 amended and integrated by Presidential Decree 120 of 12 March 2003.

Purpose of the Habitat Directive it is "safeguarding biodiversity by conserving natural habitats, as well as wild flora and fauna in the European territory of the Member States to which the Treaty applies" (art. 2). To achieve this objective, the Directive establishes measures aimed at ensuring the maintenance or restoration, in a satisfactory state of conservation, of the habitats and species of Community interest listed in its annexes. The implementation of the Directive took place in Italy in 1997 through the DPR Regulation 8 September 1997 n. 357, modified and integrated by Presidential Decree 120 of 12 March 2003. The wolf is present in Annex II and Annex IV of the Habitat Directive (which correspond to Annex B and D of Presidential Decree 357/97). In particular, Annex II refers to animal and plant species of community interest whose conservation requires the designation of special areas of conservation (SACs), while Annex IV contains the animal and plant species of Community interest which require strict protection.

In order to better understand the issue of legal wolf withdrawals, it is necessary to make a clarification with respect to the previous paragraph.

The Spanish populations north of the Duero, the Greek populations north of the 39th parallel, the Finnish populations within the rangiferous heritage management area as defined in paragraph 2 of Finnish law no. 848/90, of 14 September 1990, the Bulgarian, Latvian, Lithuanian, Estonian, Polish and Slovakian populations are not included in Annex IV of the Habitats Directive but inannex V of the same Directive, which includes animal and plant species of Community interest the withdrawal of which in kind and the exploitation of which could be subject to management measures.

According to article 19 of the Directive “The changes necessary to adapt Annexes I, II, III, V and VI to technical and scientific progress are adopted by the Council, which decides by qualified majority on a proposal from the Commission. The changes necessary to adapt Annex IV to technical and scientific progress are adopted by the Council, acting unanimously on a proposal from the Commission ".

For an exhaustive discussion of the Italian and European standards, and of the technical documents in which the wolf is referred to, see chapter 4 of the brochure published by ACT "THE WOLF: Brief analysis on the status of the wolf, on the legislative / management aspects in Europe and on the impact of predation on ungulates in the Province of Trento", available here.

Wolf management in France, Austria and Slovenia

It is not possible to describe in detail all the actions that are taken in relation to the management of the wolf in other countries in a short article like this one. However, we have tried to bring out some interesting aspects, asking the researchers who work with this large carnivore some questions.

We have integrated the answers of the experts by adding some other information that we believe useful to better understand the dynamics of the species in these countries, and links for further information.

The questions asked to the researchers were:

1. How is the wolf managed in your country? Is wolf hunting / killing legal and under what circumstances? Since wolf hunting / killing has become legal, in which cases is it possible to hunt wolves and what are the permitted killing quotas?

2. Did you (or the local management body) assess whether wolf culling had a positive effect in reducing predation on livestock and decreasing the trend in increasing wolf numbers over time? If you have no data, what is your idea / opinion about this effect?

3. Did you (or the local management body) assess whether wolf killing had a positive effect on human attitudes towards wolves or not? If you have no data, what is your idea / opinion about this effect?

France

Answer to question 1 (management and legal killing of wolves).

Wolf management in France is planned and conducted at the national level and consists of two main aspects: monitoring the abundance and distribution of the wolf in the country and managing the impact of the species on livestock. France is implementing the fourth version of his National action plan on wolf and breeding activities 2018-2023, while the first national management plan dates back to 2001.

Wolf monitoring in France is based on a national network of trained observers, distributed in all areas where the species is present. Network members collect data on wolf signs of presence (droppings, sightings, etc.) in their sampling area and report to the public body responsible for monitoring, which then estimates wolf abundance and distribution using a variety of methods and models. Reports on the situation of the species in the country are published every six months following monitoring campaigns in winter and summer. The abundance is estimated through capture-marking-recapture analyzes on genetic data obtained by non-invasive sampling. However, given the continued expansion of the species in the country, abundance is increasingly difficult and expensive to estimate.

Therefore, alternative and less expensive methods for wolf monitoring, based on spatial distribution rather than absolute numbers, are being studied.

The management of livestock predation in France has three components: compensation to breeders, financing of preventive measures and lethal control of wolves under the derogatory regime of the Habitat Fauna and Flora Directive of 1992, in order to prevent major damage from predation.

Compensation for direct and indirect losses is funded by the ministry responsible for environmental affairs and is based on expert assessments in the field in the event of suspected wolf predation events.

Breeders are entitled to compensation if wolf predation cannot be ruled out as a cause of livestock death. In addition, sheep farmers are required to put in place at least two preventive measures against predation of the three recommended (i.e. electrified fences, livestock guarding dogs and shepherds), unless they operate in a place or manner deemed by local authorities too difficult to defend against predation.

For cattle breeders, the compensation is not conditional on the presence of preventive measures.

Over 90% of wolf predation in France is from sheep farms, although attacks on cattle are on the rise. Preventive measures are funded by the ministry in charge of agricultural affairs and five options are available for farmers: shepherds, LGDs, electrified fences, analysis of vulnerability to attack by large carnivores and technical support. The amount of funding available for each of these options (from 80 to 100%) depends on the level of predation pressure to which the farmer is subjected: four "levels" of increasing predation pressure are identified, and each year farmers have access to increasingly larger funds depending on the increase in the level of predation pressure.

The wolf is a strictly protected species in France following the transposition into national law of the provisions of the 1979 Bern Convention and the 1992 EU Habitats, Fauna and Flora Directive. However, the Habitats Directive it also allows for exemptions from this protected status to prevent serious damage to livestock, when no other satisfactory solution is available and the favorable conservation status of the species is not threatened. It is under this regime that in France the killing of the wolf is practiced: the terms and conditions of how it is performed (i.e. by whom, when, where and with what material) are defined based on the extent and occurrence of predation damage to livestock, and is also based on pressure "levels" of predation, as reported above.

In areas with the lowest level of predation pressure, breeders have the right to employ only non-lethal means to keep wolves away from their livestock. In areas where there is from a minimum of one predation event in five years to three predation events in a year, a breeder holding a hunting license or a hunter specially designated by the local authorities has the right to execute shots. lethal. Where more than three predation events occur in a given year, multiple shooters can participate in the shootings, all with a hunting license.

The killing takes place mainly in the immediate vicinity of the herd to be protected, but exceptionally hunting trips can also be organized to kill wolves if deemed appropriate by the local authorities.

The French state has also set up a wolf control unit that intervenes in areas where the pressure of predation is high, despite the use of preventive measures by the farmer (at least two out of three measures taken, as described above), or in areas where the use of preventive measures is recognized by local authorities as too difficult to implement.

Wolf culling is not allowed in protected areas such as national parks and wildlife reserves, regardless of the presence of predation events.

Wolf culling in France has been carried out since 2011: a maximum number of wolves that can legally be killed is set in advance, calculated each year on the basis of abundance data and population conservation projections.

This maximum number of wolves that can be killed is in any case less than the value of the average population growth rate, and is currently set at 19% of the population size, but could increase up to 21% in any given year if deemed necessary and appropriate by the authorities, in accordance with subsequent population monitoring estimates showing that such an increase will not adversely affect on the rate of population growth. The number of (known) wolves that are killed illegally are deducted from the maximum number of wolves that can be killed, while the number of wolves that die of natural or accidental causes are recorded but not subtracted.

In 2021, the maximum number of wolves that can be killed in France is 118 (currently an estimated 624 individuals present): Figure 1 shows the number of wolves killed in France since 2018.

Wolf hunting as a leisure activity, as opposed to killing to protect livestock, is currently not allowed in France.

Figure 1. Number of wolves killed in France from 2018 to 2021 (up to September). In blue the maximum rate that can be killed, in orange the wolves actually killed, in gray the wolves killed illegally (DREAL-AuRA data, provided by the working group of the Office Français de la Biodiversité - OFB, France).

Answer to question 2 (possible effects of the slaughter on predation and wolf population trends).

In France, a doctoral thesis on the effect of wolf killing in reducing predation on livestock is nearing completion.

Preliminary results generally suggest that lethal control is effective in reducing livestock predation, but mainly only for a short period of time, ie for a few days after culling.

More specifically, the analysis of observed data on predation levels and wolf culling in France suggests that the effects of killing are highly variable depending on the context (for example they depend on position, altitude, season, sex of the killed wolf, etc.): in particular on the basis of different scientific studies it is found (Figure 2) that, although in most of the contexts observed the killing of wolves has led to a reduction in predation (58%), there are also situations in which the killing has in fact had no effect (17%) and, in some situations, there was even an increase in predations (25%).

Figure 2. Effects of abatements on the frequency of predations, identified by 12 scientific analyzes: in red increase in predation (25%), in green decrease in predation (58%), in gray no effect found (17%) (from Oksana et al., 2020).

The displacement of predations to nearby places following a culling seemed to occur occasionally.

These results show that the effects of wolf culling on predation vary according to the context and that the management of the species must be adapted according to the various human contexts and according to the various breeding practices.

Currently the monitoring of the species, together with the population growth patterns in France, seem to show that the number of wolves in France is still increasing, albeit more slowly than a few years ago (about a rate of 8% per year, both as the number of individuals, shown in Figure 3, and as the number of flocks) and with a higher turnover rate of individuals than in previous years.

With the management set in recent years (and in particular since the maximum withdrawal is set at the values of 19% of the estimated population, with the possibility of reaching up to 21% in certain situations), the survival rate of wolves has dropped to to approach values that would lead to a decrease in the population in the medium term.

Answer to question 3 (possible effects of the abatement on people's attitudes).

No evaluation of the effect of wolf culling on human attitudes towards wolves has been formally conducted in France.

Therefore, giving an opinion, even if an expert one, on this topic would be risky and certainly biased according to one's preconceived ideas on the subject and / or knowledge of results found elsewhere.

However, it is probably fair to say that the current wolf culling policy in France is unsatisfactory for many stakeholders: some argue that culling is too limited and should be expanded, while others argue that the practice is unethical and ineffective in deterring large-scale predation.

However, a more pragmatic viewpoint considers wolf removal as a management tool among others, to be used in the short term in predation hot spots when needed, also focusing on implementing long-term preventive measures and ensuring that the dynamics of the population of the species nevertheless remain positive within France.

Figure 3. Trend of the wolf population in France, based on the estimates with the capture-marking-recapture method on genetic data obtained by non-invasive sampling. For the winter of 2020/21 the projection is of an average value of 624 wolves present (the interval 414-834; image source).

Austria

Answer to question 1 (management and legal killing of wolves).

Austria is a member state ofXNUMX-XNUMX business days and therefore the Habitat Directive. The wolf is listed in Annex IV for Austria and therefore strictly protected: the exceptions to this strict protection pursuant to art. 16 are possible, including killing.

In Austria, nature conservation and wildlife management are legally organized at the state level (nine states): in six states the wolf is listed only in the hunting law, in two states both in the nature conservation law and in the law on hunting. hunting, and in one state only in the nature conservation law. So far, no wolves have been killed, although some states aim at this due to increased damage to sheep on alpine pastures: nevertheless often sheep predation affects flocks not protected by preventive measures and therefore a discussion is underway whether legal exceptions to strict protection are possible even in these circumstances.

Answer to question 2 (possible effects of the slaughter on the trend of predation and the wolf population) and 3 (possible effects of the slaughter on the attitude of the people).

To date, no legal abatement has been authorized, pursuant to art. 16 of Habitat Directive, there is no experience regarding the possible effects on predation and people's attitudes.

Authors' note: in the time elapsed between the answer given by the researchers and the release of this article, the news arrived that the Tyrolean agriculture councilor Josef Geisler authorized the killing of a wolf, on the basis that this specimen would have killed 53 sheep in four months, in an area close to the Stams monastery: this is the first time that a wolf has been declared "fetchable" in Tyrol.

However, following the appeal by various NGOs (non-governmental organizations), the provincial court has suspended the culling, and the matter will go to the Supreme Court. For more info go here e , promising

Slovenia

Answer to question 1 (management and legal killing of wolves).

In Slovenia, the wolf is a strictly protected species, exceptional culls are authorized which allow to reduce particularly intense conflicts with breeding, hybridization with domestic dogs and to ensure the health and safety of people.

Permits for such exceptional killing are issued by the Ministry responsible for nature conservation (currently the Ministry of the Environment and Territorial Planning) and must be in line with the views of experts from the Slovenian Forest Service and the Institute of the Republic of Slovenia for Nature Conservation.

Legal wolf hunting has not been practiced in Slovenia since 1990, when this species became protected by the Hunting Association of Slovenia, until 1999, when the population was once again huntable. For each year (except 2000 and 2008), the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (since 2005 the Ministry of the Environment and Territorial Planning), has issued permits for the selective and limited removal of some animals under strictly controlled conditions. and in limited numbers.

In 2016 and again in 2018, NGOs filed a lawsuit against the Republic of Slovenia to stop the killing of wolves: since then, wolf culls have been carried out on the basis of individual permits and no longer as a predefined quota of wolves that could be culled.

Since 2015, the Slovenian Ministry of the Environment has financed national monitoring projects, compensates for damage caused by wolves and finances measures to prevent damage to livestock.

Figure 4. Trend in the number of wolves dead in Slovenia from 1995 to 2020, considering both legal culls and deaths from other causes (data provided by the working group of Slovenia Forest Service, Slovenia).

Answer to question 2 (possible effects of the slaughter on predation and wolf population trends).

The assessment of the effect of wolf culling on livestock predation was carried out in 2010 as part of the LIFE SloWolf project for the area where the wolf was permanently present at that time. This study analyzed the correlation between the data relating to the culling of wolves and the predation events on livestock between 1995 and 2009: in the time span of 15 years the number of wolves killed has fluctuated considerably from year to year (from 0 to 10 per year).

A total of 51 wolves were culled, representing 82% of all recorded mortality among wolves.

In the evaluation period, 2221 episodes (10 to 432 per year) of wolf attacks on pets were recorded, with an estimated damage of 1,4 million euros.

Correlation analysis revealed no effect of wolf culling on the level of predation events. No effect was also observed when the years in which a high number of wolves were killed were compared. When compared with several variables, the extent of the damage was more correlated with the number of sheep in Slovenia.

The influence of wolf culling on wolf dispersal in new areas (e.g. Alpine and pre-Alpine areas) has not been analyzed.

Through the literature review, the aforementioned study also points to some examples where wolf culling can be considered an at least effective measure to reduce livestock predation. The first of these cases would be the elimination of an entire population of wolves or the removal of most of the wolves from a large area: such a drastic measure could be used in the case of a zoning, impossible to achieve in a small country like Slovenia.

The second example reported by the authors of the study is the killing of wolves near cattle grazing areas: in theory this type of killing could serve as a lesson to the other individuals in the pack, since the wolf is a very intelligent social animal, and reconnect the fact that pasture is a dangerous place. However, the correct implementation of this killing is very demanding in practice (for example: avoiding the killing of reproductive animals, the considerable effort in the field required to carry out this killing, the effective and quick bureaucracy for the issue of killing permits).

In addition to this, the 2010 study also highlights some indirect effects of culling such as the possible decrease in the illegal killing of wolves, the negative effect on the social structure of the pack and the possible greater hybridization with domestic dogs.

Finally, it is also considered that a total ban on culling in some way precludes the participation of the local population in the decision-making process.

In any case, we think wolf killing shouldn't be the only measure to prevent livestock predation events and that should be promoted the implementation of other non-lethal protective measures, while it could be an important part of managing the removal of particularly critical individuals and hybrids.

Figure 5. Trend of the estimate of the number of wolves present in Slovenia alone (in black) and also considering the transboundary wolves with Croatia (in red); image source.

Answer to question 3 (possible effects of the abatement on people's attitudes).

Two surveys have so far been conducted in Slovenia to understand the general public's attitude towards wolf conservation and management.

The first survey was carried out within the project LIFE SloWolf in 2011 and the second in the context of national wolf monitoring project in 2020.

In the following paragraphs we will focus on the latter, as it concerns the latest data on human attitudes we have. The 2020 survey questionnaire consisted of 47 questions covering a wide range of topics related to wolf conservation and management: the results of this study are based on 733 returned and fully completed questionnaires.

In connection with the above question, the section of the questionnaire that addressed public attitudes towards management measures offers some insights into public opinion on wolf culling. In this section we asked the participants to give their opinion on two statements related to the number of wolves: "We have too many wolves in Slovenia" e "The number of wolves in Slovenia should increase".

The answer shows that, despite a positive attitude towards the wolf, the respondents do not want further population growth.

47,9% of respondents agree with the statement that there are too many wolves in Slovenia and 31,6% disagree. Considering the second statement, 65,1% of the respondents disagree that the number of wolves in Slovenia should increase and 9,8% of the respondents agree with this statement.

In addition to this, two other statements focused directly on the killing of wolves: "Wolves in Slovenia should be fully protected (shooting wolves should be prohibited)" e "If a wolf attacked livestock, I would accept its exceptional slaughter". The responses show that the public does not want to ban culling and also supports the culling of wolves in case the wolves cause harm to pets. Indeed, 62,1% of respondents disagree with the statement that wolves should be fully protected in Slovenia, while 27,7% believe that full protection is needed and are against culling. 62% of respondents agree with the claim about killing wolves causing damage, while 5,7% argue that damage is not a reason for killing.

Figure 3. Trend of the wolf population in France, based on the estimates with the capture-marking-recapture method on genetic data obtained by non-invasive sampling. For the winter of 2020/21 the projection is an average value of 624 wolves present (the interval 414-834; image source).

Thanks

We thank the research groups of France, Austria and Slovenia for answering the questions and providing useful information to obtain a picture of the management situation of the wolf in their countries.

In particular: Ricardo Simon, Christophe Duchamp, Nolwenn Drouet-Hoguet and Nicolas Jean (Office Français de la Biodiversité - OFB, France); Theresa Walter and Felix Knauer (Vienna Vetmeduni University of Veterinary Medicine, Austria); Gregor Simčič and Rok Cerne (Slovenia Forest Service, Slovenia).

We also thank Miha Krofel (University of Ljubljana, Slovenia) for providing useful information in writing the article.

REFERENCES

- Cesco Frare P., 2000 Tunin and the Wolf. The Belluno Dolomites Christmas 2000. Ed. CAI Belluno: 30-34.

- Krofel M., Cerne R., Jerina K. (2011). Effectiveness of wolf (Canis lupus) culling to reduce livestock depredations. Acta Silvae et Ligni. 95. 11-22.

- Lapini L., Brugnoli A., Krofel M., Kranz A., Molinari P., A gray wolf (Canis lupus Linnaeus, 1758) from Fiemme Valley, «Bulletin of the Natural Science Museum of Venice», 61 (2010), pp. 117-129.

- Grente O., Duchamp C., Bauduin S., Opitz T., Chamaillé-Jammes S., Drouet-Hoguet N., Gimenez O. (2020), Tirs dérogatoires de loups en France: état des connaissances et des enjeux pour la gestion des attaques aux troupeaux Faune Sauvage n ° 327

- Tormen G., Catello M., Cesco Frare P., Historical presence and toponyms on the wolf (Canis lupus Linneaus, 1758) in the province of Belluno, "Natura Vicentina", 2003, n. 7, pp. 259-265.

- Treves A., Krofel M., McManus J. (2016) Predator control should not be a shot in the dark. Front Ecol Environ 14 (7): 380–388.

- http://www.auvergne-rhone-alpes.developpement-durable.gouv.fr/mission-loup-r1323.html

- http://www.comelicocultura.it/0800×0600/Italiano/Letteratura_Proverbi/tunin_ed_il_lupo.htm

- https://www.loupfrance.fr/wp-content/uploads/Article-Faune-sauvage-tirs-derogatoires-de-loups-en-France.pdf